|

Scroll down for English version Una chiacchierata con Steven Brown su Musica, Imperialismo, Vita e Resistenza Tra il 24 maggio e il 5 giugno Steven Brown ha girato l’Europa per presentare il suo nuovo album “El Hombre Invisible”. Venerdì 27, in occasione del suo concerto a Romano d’Ezzelino per il festival “Le notti del bandito” ho avuto modo di parlare con il mitico fondatore dei Tuxedomoon di varie cose. Ecco come è andata. |

||

|

Il soundcheck è terminato. Sono le sei di sera, ma è fine maggio e il sole è ancora alto nel cielo. C’è questa pizzeria a pochi passi dal teatro, ed è già aperta. Ci sono quattro o cinque tavoloni da sagra sulla terrazza che dà sulla strada: Steven Brown ordina una pizza vegetariana e una bottiglia di acqua naturale. Possiamo iniziare. A&B: Questo è il tuo primo album da solista dai tempi di “Half Out”, nel 1991. Cosa hai fatto da allora?

L’Uomo Invisibile Mi tengo per me il pensiero che Steven Brown non ha menzionato i cinque album che ha registrato negli stessi anni con i Tuxedomoon, e che sono peraltro tra i miei preferiti, ovvero Joeboy in Mexico (1997), Cabin in the Sky (2004), Vapor Trails (2007), Pink Narcissus (2014) e Blue Velvet Revisited (con i Cult With No Name, 2015), e passo subito alla mia domanda successiva. A&B: Il tuo nuovo album si chiama “El Hombre Invisible”. E quindi la mia domanda è: chi è l’uomo invisibile? Chi sono gli uomini invisibili?

Steven (ridacchia, poi risponde): In un certo senso sì, in un certo senso. Inoltre, vedi, in un’interessante intervista l'attrice francese Juliette Binoche ha detto che nella società odierna gli anziani e i poveri sono invisibili, ho pensato che questa fosse una cosa molto acuta e importante da dire, ed è una cosa che posso capire bene.» [NDR: intervista a Juliette Binoche in occasione dell’uscita nel 2022 del film “Tra due mondi” di Emmanuel Carrère] A&B: Nella canzone eponima “El Hombre Invisible” dici “Quiero asistir a un baile inesistente / I want to show you The Invisible Man”. Perché questo ballo in realtà non esiste? Steven (ridacchia di nuovo): Ormai non mi piacciono più i posti dove andare a ballare perché sono troppo vecchio… e quindi mi piacciono i danzatori invisibili. Ho l’impressione che ci sia dell’altro, ma è anche vero che ho molto altro da chiedere. Passiamo oltre. Il più pericoloso Libro del mondo e l’eredità del Neozapatismo A&B: Se non sbaglio il tuo album “Joeboy in Mexico” (1997) inizia con la voce del Subcomandante Marcos ad un comizio mentre dice “contra la dictadura, contra el autoritarismo ... contra la corrupcion, contra el patriarcado etc etc”. Poi nella canzone “Lawnmoaner” dall'album “Rain of Fire” che hai registrato con i Nine Rain nel 2001, dici “il mondo cambierà quando gli esseri umani inizieranno a parlare con i nostri cuori e non con le nostre lingue, dicen los Zapatistas”, e ora nella canzone “The Book” del tuo nuovo album parli dell’eterna e sanguinosa storia di sopraffazione dopo sopraffazione: conquistatori spagnoli che massacrano i nativi americani, e poi gli inglesi che uccidono gli spagnoli, e così via, in nome del Libro. Allora, qual è l’eredità per il XXI secolo, sempre che ce ne sia una, dei moderni zapatisti e del subcomandante Marcos? Steven: Ciò che canto nella canzone “The Book” è un fatto storico: a quel tempo gli spagnoli erano già in Messico e si trovavano in questa città di nome Campeche, gli inglesi l’hanno conquistata e hanno ucciso tutti: uomini, donne, bambini. Hanno bruciato la città e ucciso tutti. Perché tutto ciò? A causa del Libro. Il libro è la Bibbia: gli spagnoli uccisero gli “Indiani” perché loro credevano nel loro Dio e per loro gli “Indiani” erano il diavolo. Ma in seguito gli spagnoli furono uccisi da altri cristiani europei, e quindi si deve tutto alla Bibbia, il libro più pericoloso [NDR: nel XVII secolo i pirati condussero molteplici attacchi a Campeche al servizio o comunque nell'interesse della Corona inglese, il più grave dei quali fu il sacco del 1685]. Quindi tu vuoi conoscere la lezione che potremmo imparare dagli zapatisti e applicare ad altri paesi. Eccola: è l’autonomia. Gli zapatisti dicono: “Guarda quello che facciamo e fallo dove vivi”. È una questione di autonomia e di persone che vivono in comunità e non si preoccupano del consumismo e non si preoccupano dei politici né dei partiti politici. C’è un piccolo movimento che sta crescendo in Messico in cui le città cacciano via la polizia, cacciano via i politici e si autogovernano tra di loro. Non vogliono il potere, vogliono solo essere lasciati soli. E si tratta di comunità autonome. Ecco di cosa si tratta, ed è qualcosa che sta per accadere anche in Europa».

L’impero visto dai margini A&B: Cosa significa per te, in quanto artista e attivista originario degli Stati Uniti vivere, diciamo così, ai margini dell’Occidente? C’è qualcosa che capisci meglio ora riguardo agli Stati Uniti e all'Europa occidentale rispetto a quando ci vivevi Steven: Beh, anche quando vivevo negli USA ero consapevole di tutto quello che non andava negli USA. Ora che non vivo più lì, vedo sia le cose belle che quelle brutte, ma le cose brutte degli States le ho sempre viste. A 16 anni [NDR: nel 1968] ho girato un documentario su questi nativi americani che avevano occupato un laboratorio nucleare fuori Chicago e ne avevano reclamato il terreno su cui sorgeva come loro territorio. Io vado tra loro, faccio il mio documentario breve e capisco di avere un’affinità con loro. E qualche tempo dopo ero presente alle manifestazioni a Chicago in seguito all’omicidio di Fred Hampton delle Pantere Nere [NDR: la morte di Hampton il 4 dicembre 1969 è considerata dalla maggior parte degli studiosi un assassinio organizzato dall’FBI nell’ambito del programma COINTELPRO]. Ho protestato contro la guerra in Vietnam e nel 1972 a Washington DC sono finito in carcere perché protestavo contro la guerra. E ora che vivo fuori dagli USA mi dispiace di non essere riuscito a cambiare davvero l’America, che era ed è tuttora una potenza imperialista. E ora in Canada c'è questo grosso problema delle miniere che stanno aprendo in tutto il paese, distruggono l’ambiente e portano via tutti i soldi, non pagano tasse locali e quindi è sfruttamento puro e semplice. E intanto gli spagnoli producono elettricità con le centrali eoliche messicane e si portano tutti i profitti a casa in Spagna. E quindi è davvero di nuovo come ai tempi della conquista dell’America: non è cambiato molto». La Cinema Domingo Orchestra di Oaxaca A&B: Parliamo della tua attuale esperienza di sonorizzazione di vecchi film con la Cinema Domingo Orchestra. Come sta andando? Steven: Abbiamo fatto un concerto poco prima che venissi qui in Europa. Ne facciamo un po’ in tutto il Messico. Periodicamente poi, qualche festival ci propone un film da sonorizzare. Inoltre l’Istituto Messicano del Cinema ci ha ingaggiato in 2 occasioni per realizzare la colonna sonora di film che avevano restaurato da poco, come i film tedeschi degli anni ’20. In particolare ne abbiamo sonorizzato uno di Fritz Lang, il film Destiny. Suoniamo sia in piccoli posti nella zona di Oaxaca sia in vari teatri messicani, all’aperto e al chiuso. Tutto ha avuto iniziato nel giardino di casa mia come un passatempo per i fine settimana. Sai, abbiamo creato una cosa simile alle T.A.Z. degli anarchici, una zona autonoma temporanea. Inizialmente, 20 anni fa, era qualcosa tipo “proiettiamo un film e suoniamoci sopra”. A poco a poco è diventata una cosa più seria: abbiamo iniziato a scrivere musica per i film invece di limitarci a improvvisare, e così ora abbiamo un repertorio di 10-12 film con le loro colonne sonore. Quindi ora è diventata una seria attività professionale: ci esibiamo in tutto il paese nei teatri, proiettiamo il film e suoniamo la colonna sonora». Solo un sogno? A&B: Permettimi di farti una domanda forse curiosa. Alla fine della canzone “Raw Girls” dal tuo primo album con i Nine Rain canti “e il titolare chiede un’offerta, e dice: ‘tu paghi, tu paghi per il privilegio di avere passato il tuo tempo qui’”. Chi è il titolare? Dio, il Potere, l’Impero? Steven: No, si trattava solo di un sogno in cui c’è un club, e non paghi per entrarci, ma per uscire dal club devi pagare. Era solo un sogno, tutto qui. Sono assolutamente sicuro che ci sia molto altro da dire su quel sogno trasformato in canzone, e che in qualche modo abbia a che fare con il concetto stesso di esistenza per Steven Brown. Ci sono questi versi di “Raw Girls” che continuano a risuonare nella mia mente: “Mi trovo in una casa su una collina che è un club, che è il mondo, che è la vita, e tutti ci passano ad un certo punto... Ricordati, di quando c’era la vita / Ricordati, di quando nulla era banale / Ricordati, di quando i minuti trascorsi ad aspettare un autobus erano pieni di stupore / Ricordati, di quando eri completamente consumato dalla pura gioia del processo della vita stessa”. È ora di porre la mia ultima domanda, qualcosa che riguarda la vita stessa e la resistenza, sia come individui che come comunità. Vita e Resistenza A&B: Ai tempi delle guerre nei Balcani l'architetto, filosofo e attivista americano Lebbeus Woods si trovava a Sarajevo. La sua esperienza in Jugoslavia lo ha portato alla convinzione che dovranno essere le eterarchie invece che le gerarchie il modo migliore per ricostruire le comunità dal basso – una posizione molto zapatista, oserei dire. Inoltre, ha redatto una dettagliata Checklist della Resistenza e nel suo saggio “War and Architecture” (1993) ha scritto: “Io sono in guerra con il mio tempo, con la storia, con ogni autorità che risiede in forme fisse e paralizzate dalla pauta. Io sono uno dei milioni di persone che non si adattano, che non hanno casa, famiglia, dottrina, nessun luogo definitivo da chiamare ‘mio’, nessun inizio o fine conosciuti, nessun ‘luogo sacro e primordiale’. Io dichiaro guerra a tutte le icone e finalità, a tutte le storie che mi avrebbero incatenato alle mia stessa falsità, alle mie stesse pietose paure”. E quindi, qual è la tua posizione sulla Resistenza? Steven: Perché penso che Jean-Luc Godard debba essere un fan di questo tipo? Wow, a parte gli scherzi: queste cose avrei potuto scriverle io!

A&B: Nella tua canzone “Resist” da “El Hombre Invisible” riaffermi infatti che non hai altra scelta che resistere. Cosa intendi per resistere? Steven: Non c’è altra scelta che resistere. Io non ho altra scelta che resistere perché non so adattarmi alla maggior parte della società. Sai, nella casa che ho costruito in Messico tutto viene riciclato. L’ho costruita con servizi igienici a secco. Risparmiamo e recuperiamo l’acqua: ottengo acqua dal kit di riciclo del lavandino del bagno. Successivamente l’acqua della doccia finisce in giardino filtrata, non nei fiumi. L’acqua calda la ottengo dai pannelli solari. Anche questo è un modo di resistere. La mia Resistenza è vivere la mia vita e non essere parte di un sistema in cui non credo. E, ogni volta che è possibile, unirmi agli altri nella lotta per creare un mondo diverso. Sono stato in Chiapas, ho suonato con i Nine Rain nelle comunità zapatiste negli anni ’90. Lo sai, ogni volta che ci sono manifestazioni cerco di contribuire con il mio granello di sabbia. Lo faccio in qualsiasi movimento che penso vada nella giusta direzione. Non è niente di così particolare o difficile, insomma, non sono un rivoluzionario, provo solo a farlo. E mi viene naturale. Questo è quello che sto cercando di dire: io non ho scelta perché resistere mi sembra naturale, esattamente come bere e mangiare. Resistere fa parte della mia vita. Finiamo di mangiare le nostre pizze. Ora il sole è al tramonto. Steven Brown va a riposarsi un paio d’ore prima del concerto. Sarà un grande set, 15 canzoni più i bis a riassumere, in un certo senso, cinquant’anni di Resistenza in una notte. * Ringrazio Ludovica Furlan per l’aiuto durante la registrazione dell'intervista a Steven Brown. A talk with Steven Brown on Music, Imperialism, Life and Resistance Between May 24th and June 5th Steven Brown has toured Europe to present his new album “El Hombre Invisible”. Friday 27, on the occasion of his concert in Romano d'Ezzelino for the festival “Le notti del bandito” I had the opportunity to talk with the legendary founder of Tuxedomoon about various things. Here’s how it went. The soundcheck has finished. It’s six in the evening, but it’s the end of May, and the sun is still high in the sky. There is this pizzeria a few steps from the theater, and it’s already open. There are four or five festival tables on the terrace overlooking the street: Steven Brown orders a veggie pizza and a bottle of still water. We can start. A&B: This is your first solo album since “Half Out”, in 1991. What have you being doing since then? Steven: I’ve made many records in Mexico in the last three decades with different groups, starting with Nine Rain, which I founded when I got there in 1994. I made five records with them, and then I moved to Oaxaca, where I made another three or four records: the soundtrack for the documentary “El Informe Toledo”, an album with the Ensamble Kafka, and the sonorizations of films with Cinema Domingo Orchestra (ed.: “Optical Sounds”, 2018). Moreover, in Oaxaca I made two records with a group of indigenous musicians, they’re called the Banda Regional Mixe. But most people outside of Mexico don't know these records…» The Invisible Man I keep to myself the thought that Steven Brown has not mentioned the five albums he recorded in the same years with Tuxedomoon, and, which, by the way, are among my favorite ones, namely Joeboy in Mexico (1997), Cabin in the Sky (2004), Vapour Trails (2007), Pink Narcissus (2014) and Blue Velvet Revisited (with Cult With No Name, 2015), and I move straight to my next question. Steven: I am the invisible man. There was a book written in the 50s by a man named Ralph Ellison. He was a Black American author. He wrote this book called “The Invisible Man” referring to being a black man in the United States: as a black man in the white society he felt like he was invisible. A&B: So this is much like a metaphor… or perhaps, ehm, do you feel just like him now? Steven (chuckles, and then answers): In a way, yes, in a way. Also, you see, there was an interesting interview with the french actress Juliette Binoche in which she said that in today’s society old people and poor people are invisible, and so I thought that was a very acute and important thing to say, and I can relate to that.» [ed.: interview with Juliette Binoche on the occasion of the release in 2022 of the movie “Ouistreham” by Emmanuel Carrère] A&B: In the eponymous song “El Hombre Invisible”, you sing “Quiero asistir a un baile inexistente / I want to show you the Invisible Man”. Why does this dance actually not exist?» Steven (chuckles again): I don’t usually like places to go to dance anymore because I’m too old and so I like invisible dancers. I have the impression that there is more, but it is also true that I have much more to ask. Let’s move on. The most dangerous Book in the world and the Legacy of Neozapatismo A&B: If I’m not mistaken your album “Joeboy in Mexico” (1997) starts with the voice of Subcomandante Marcos saying “contra la dictadura, contra el autoritarismo… contra la corrupcion, contra el patriarcado etc etc”. Then in the song “Lawnmoaner” from the album “Rain of Fire” you recorded with Nine Rain in 2001, you say “the world will change when human beings begin to speak with our hearts and not with our tongues, dicen los Zapatistas”, and now in the song “The Book” from your new album you talk about the eternal and bloody history of suppression after suppression: Spanish conquerors who suppress the native Americans, and then the English who kill the Spanish, and so on and on, in the name of the Book. So, what is the legacy for the 21st century, if there is any, of modern Zapatistas and Subcomandante Marcos?» Steven: What I sing in the song “The Book” is historical: the Spanish were in Mexico already and they were in this city called Campeche, and the English came in and killed everybody in the city, men, women, children. They burned the city down and killed everybody. Why that? Because of the book. The book is the Bible: the Spanish killed the “Indians” because they believed in their God and the “Indians” were the devil. But later the Spanish were killed by other Christian Europeans. So it’s all about the Bible, the most dangerous book [ed. In the 17th century pirates conducted multiple attacks to Campeche in the service or otherwise in the interest of the English crown, the most serious of which was the sack of 1685]. So, you want to know the lesson we could learn from Zapatistas and apply to other countries. It’s autonomy. The Zapatistas say “Look at what we’re doing and do it where you live”. It’s a question of autonomy and people living in communities and not being concerned with consumerism and not being concerned with politicians and political parties. There’s a small movement that’s growing in Mexico where towns throw out the police. They throw out the politicians and they just govern themselves amongst themselves. They don’t want power, they just want to be left alone. And they’re autonomous communities. That’s what it’s all about, which is also happening in Europe.» The Empire seen from the margins A&B: What does mean for you as an artist and an activist coming from the United States to live, let’s say, at the margins of Western countries? What do you now understand better regarding the U.S. and Western Europe as compared to when you lived in there? Steven: Well, even when I lived in the States I was aware of everything that was wrong with the States. Now that I don’t live there, I see both the good things and the bad things, but I always saw the bad things of the States. I was 16 years old [ed.: in 1968] and I made a documentary about these Indigenous who had taken over a nuclear laboratory outside of Chicago and claimed it was their territory. I went there and made my short documentary and I felt an affinity with them. And I was there at the demonstrations in Chicago following the murder of Fred Hampton of the Black Panther Party [ed.: Hampton’s death on December 4th, 1969, is considered by most scholars an assassination at the FBI’s initiative under the COINTELPRO program]. I went to protest against the war in Vietnam and I went to jail in Washington DC in 1972 protesting the war. So now I live outside and I’m sorry I haven’t really changed America, which was and still is an imperialist power. And now in Canada there’s this big problem because they're opening mines all over the country, destroying the environment and they take all the money away. They pay no taxes and so it’s an exploitation. And the Spanish are making electricity with mexican wind farms and taking all the profits home to Spain. So really it’s like the conquest all over again: not much has changed. The Cinema Domingo Orchestra, Oaxaca A&B: Let’s talk about your current experience of sonorization of old movies with the Cinema Domingo Orchestra. How is it going? Steven: We had a show right before I came here in Europe. We perform all over the country. Periodically, a festival will offer us a film that needs music. The Mexican Film Institute has hired us on 2 occasions to score films that they have recently restored, like early German films of the 1920s. We did one by Fritz Lang, called Destiny. We play both small places all over Oaxaca and in different Mexican theaters, outdoors and indoors. It all started in the garden of my house as something to do on a weekend. It’s like the anarchist T.A.Z., you know, a temporary autonomous zone that we created. At the beginning, 20 years ago, it was something like “let’s show a movie and make music”. Little by little it started to get more serious and we started to write music for the films, you see, instead of just jamming, and so now we have a repertoire of 10, 12 films that have their scores. So now it’s kind of a serious professional thing: we play all over the country in theaters, we show the film and play the score.» Just a dream? A&B: Let me ask you a perhaps curious question. At the end of the song “Raw Girls” from your first album with Nine Rain you sing “and the proprietor asks for a donation, he says: ‘you pay, you pay for the privilege of spending time there’”. Who is the proprietor? God, the Power, the Empire? Steven: No, that was a dream I had. In this dream there is a club, and you don’t pay to get in, but you have to pay to get out of the club. It was just a dream. I am absolutely sure that there is a lot more to say about that dream turned into song, and that it somehow has to do with Steven Brown’s very concept of existence. These lines of the song keep resonating in my mind: “I’m in a house on a hill which is a club, which is the world, which is life, everyone passes in one point or another… Remember when there was life / Remember when nothing was banal / Remember when the minutes spent waiting for a bus were filled with amazement /Remember when you were totally consumed in the pure joy of the process of life itself.” It’s time to ask my last question, something that regards life itself and resistance, both as individuals and as communities. Life and Resistance A&B: During the Balkan wars the American architect, philosopher and activist Lebbeus Woods was in Sarajevo. His experience in Jugoslavia led him to the conviction that heterarchies rather than hierarchies where the best way to rebuild communities from below, a very zapatista stance, I dare say. Moreover, he drew up a detailed Resistance Checklist and in his essay “War and Architecture” (1993) he wrote: “I am at war with my time, with history, with all authority that resides in fixed and frightened forms. I am one of millions who do not fit in, who have no home, no family, no doctrine, no firm place to call my own, no known beginning or end, no ‘sacred and primordial site.’ I declare war on all icons and finalities, on all histories that would chain me with my own falseness, my own pitiful fears.” So, what is your stance on resistance? Steven: Why I think Jean-Luc Godard must be a fan of this guy? Wow, no fun: it sounds like me!» A&B: In your song “Resist” from the “El Hombre Invisible” you indeed reaffirm that you have no choice but to resist. What do you mean by resisting? Steven: There is no other choice than to resist. I have no other choice but to resist because I don’t fit into most of the society. You know, in the house I built in Mexico everything is recycled. I built it with dry toilets. We save water: I have water from the kit from the sink in the bathroom. The shower goes into the garden through filters, it doesn’t go into the rivers. I have solar water heating. This is a way of resistance. And my resistance is living my own life and not being a part of a system that I don’t believe in. And whenever possible, joining others in this struggle to create another world. And I’ve been to Chiapas, I’ve played with Nine Rain in the zapatista communities in the 90s. And you know, like I said, whenever there’s demonstrations I just put my grain of sand. Into any movement that I think is in the right direction. It’s no big deal, I mean, I’m not any kind of revolutionary, I just try to do it, and it just comes naturally. That’s what I’m trying to say: I have no choice because it just seems natural to me, like drinking and eating. Resisting is part of my life. We finish eating our pizzas. The sun is now setting. Steven Brown goes to rest a couple of hours before the concert. It will be a great set, 15 songs plus the encore that summarize, in a sense, fifty years of resistance in one night. * Thanks to Ludovica Furlan for her help in recording the interview with Steven Brown |

||

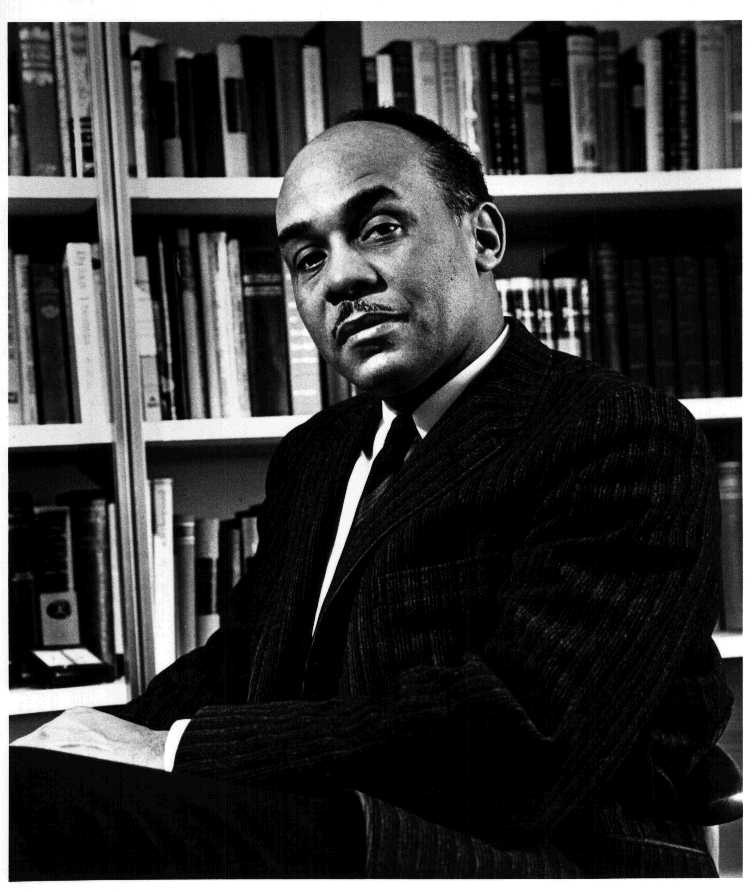

Steven Brown (Tuxedomoon)

Scritto da Leonardo Furlan Lunedì 13 Giugno 2022 17:50 Letto : 1346 volte