- SCROLL DOWN FOR ENGLISH VERSION -

Non è un segreto che “Under Milk Wood” di Dylan Thomas – uno dei radiodrammi più rivoluzionari del Secondo Dopoguerra – sia citato nei dischi “Starless and Bible Black” e “Red” dei King Crimson, avendo il suo incipit fornito al primo tanto il titolo dell’album quanto quello del settimo brano, e al secondo una potente ispirazione per il testo di “Starless”, il brano conclusivo del disco e uno dei più celebrati della band (e l’ultimo in assoluto eseguito dai King Crimson stessi, l’8 dicembre 2021 a Tōkyō). Potrebbe invece forse essere meno noto il particolare – anche se laterale – contributo dato da “A Humument” di Tom Phillips allo straordinario periodo creativo 1973-1974 dei King Crimson. Ora, siccome nessuno saprebbe darne una definizione davvero soddisfacente, credo che valga la pena introdurlo con le parole di Brian Eno: “A Humument è uno dei più originali, affascinanti e incantevoli libri di tutti i tempi”. D’altro canto, siccome bisogna pur capire di cosa stiamo parlando, dirò qui – con un certo grado di approssimazione – che questo “Monumento/Documento Umano” è un’opera d’arte – un libro d’arte, o anche un romanzo sperimentale – realizzata nell’arco di ben cinquant’anni, tra il 1966 e il 2016, e costituita da 366 pagine/tavole (più, a pagina 367, una tavola di dedica) di cui attualmente ogni comune mortale può possedere con piccolissima spesa una copia tutta a colori grazie al fatto che nel 2016 l’editore Thames & Hudson ne ha pubblicato l’edizione definitiva, versione “commerciale” (“A Humument – A Treated Victorian Novel”, Definitive Edition: Londra, 2016; ristampa 2023).

La storia, ovviamente, non finisce qui: e quindi per chi dovesse trovare intrigante la serendipità con cui talora i percorsi della letteratura e dell’arte incontrano quelli della (grande) musica, dirò ora nell’ordine 1) cosa c’entri Humument coi King Crimson; 2) come sia nato (e cosa sia) Humument; 3) cosa accade a pagina 222; 4) se, infine, ci sia qualcosa in comune tra il progetto Humument e i King Crimson.

1) Prima di tutto: cosa c’entra “A Humument” con i King Crimson?

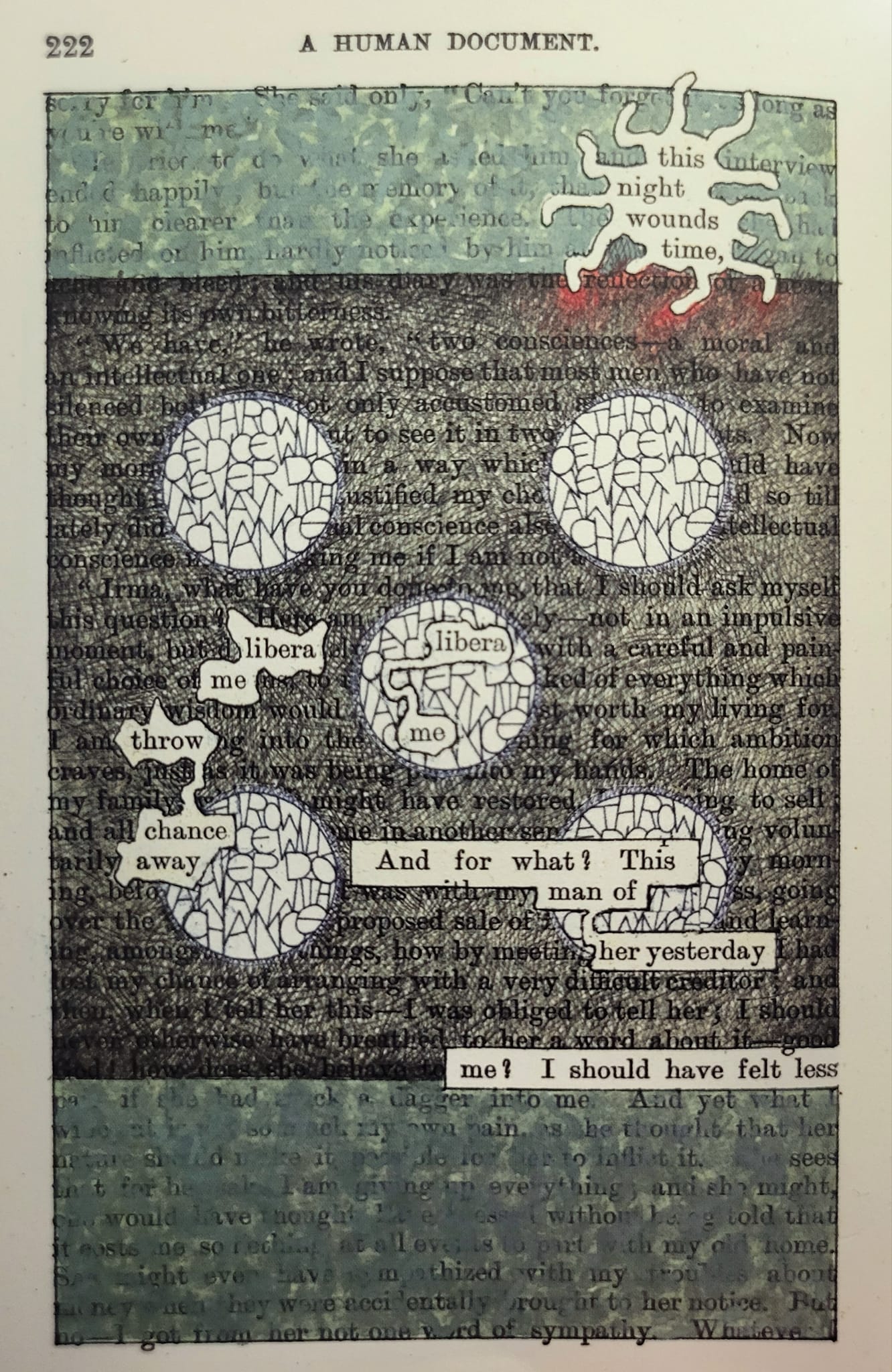

La back cover di “Starless and Bible Black” (1974) presenta al centro una scritta notissima a tutti i crimsoniani: “this night wounds time,” (“questa notte ferisce il tempo,”). La scritta si trova all’interno di quella che sembra essere una macchia di pittura bianca e a sua volta questa si trova all’interno di una tavola colorata nel cui fondo si intravedono varie lettere scarsamente leggibili.

Ecco, questo lavoro di grafica è in realtà un dettaglio della pagina/tavola 222 di “A Humument – A Treated Victorian Novel” (“Un Monumento Umano – Un romanzo vittoriano rielaborato”) di Tom Phillips, che all’epoca di “Starless and Bible Black” era stato da poco pubblicato nella sua prima edizione quasi completa (Casa Editrice Tetrad, 1973, edizione non commerciale; tra il 1971 e il 1974 la Tetrad curò la pubblicazione di tutti, diciamo così, gli “avanzamenti” dello Humument) e soprattutto era stato esposto all’Institute of Contemporary Arts di Londra (1973). Mi pare significativo che i King Crimson di quegli anni – veri avanguardisti ormai avulsi dal tradizionale mondo prog cui erano stati, più o meno giustamente, associati negli anni precedenti – abbiano scelto come cover art di SABB un’opera di frontiera che avrebbe acquistato fama e vera notorietà solo parecchi anni dopo.

2) E allora: cos’è sto “A Humument”, e da dove salta fuori?

In breve: “A Humument” è un libro scritto a cavallo tra il XX e il XXI secolo che si è mangiato un altro libro, l’opera in tre volumi “A Human Document” del romanziere vittoriano W.H. Mallock, scritto invece verso la fine del XIX secolo.

Le cose sono andate così: nel 1966, tre anni prima di “In the Court of the Crimson King” e otto anni prima di “Starless and Bible Black”, un ventinovenne grafico/pittore/stampatore di nome Tom Phillips aveva elaborato un progetto: affascinato com’era dalle esperienze letterarie di Burroughs e musicali di John Cage, voleva approfondire il ruolo del caso, della casualità, nel processo di produzione dell’opera d’arte. Per il suo progetto c’era bisogno di un grosso libro, possibilmente un romanzo, possibilmente vecchio ma ancora in buone condizioni, da “trattare”, cioè da alterare modificandone ogni pagina con tecniche di pittura, collage e ritaglio così da creare una versione completamente nuova, mantenendo leggibili solo alcune parole in ciascuna pagina e collegandole tra loro così da creare un testo nuovo.

Il 5 novembre Tom Phillips si stava aggirando in uno di quei magazzini dove sono accatastati vecchi mobili, librerie, gli avanzi con qualche valore commerciale di cantine e soffitte sgomberate, e aveva stabilito che il primo libro che avesse trovato in vendita al prezzo di tre pence sarebbe diventato il materiale base del suo progetto. Il “caso” volle che si imbattesse nel romanzo “A Human Document” di tale W.H. Mallock, 1892 (nona edizione). Phillips non aveva la benché minima idea di chi fosse questo Mallock, ma il fatto che la sua opera avesse avuto almeno nove edizioni indicava che sul finire dell’Ottocento doveva essere stato abbastanza famoso. Il fatto invece che appena sette decenni dopo fosse un autore dimenticato rendeva “il documento umano” che teneva tra le mani particolarmente affascinante. C’era poi un dettaglio squisitamente tecnico che faceva di “A Human Document” il romanzo ideale per il suo progetto: era stato stampato – come spesso avveniva all’epoca – con un’ampia spaziatura tra i caratteri, il che andava incontro quasi miracolosamente alle esigenze del giovane artista. Infine, costava esattamente tre pence, che era l’iniziale condicio sine qua non posta da Phillips!

D’altro canto il caso come fattore causale nel processo di produzione dell’opera d’arte ha rilevanza solo se si accompagna anche a un preciso sistema di costrizioni che gli dia senso (un esempio: Philip K. Dick utilizzò i “suggerimenti”/obblighi dettatigli dall’I Ching per plasmare soggetto e trama di “The Man in the High Castle” – “La svastica sul sole”), in assenza delle quali il progetto si ridurrebbe a simpatico gioco per bambini. Nel caso di “A Humument” le costrizioni sono molteplici, sia a livello grafico che testuale; mi limito qui a citare la costrizione/regola secondo cui ogni qual volta nel testo originale compare la parola “together” Phillips deve cancellare/nascondere una parte della parola (-ther) così da fare entrare in scena Toge, Bill Toge, quello che in “A Humument” è il secondo protagonista del racconto, la prima essendo Irma, già protagonista del preesistente romanzo di Mallock.

Ah, sempre sul caso: Phillips inciampò sul titolo della sua opera del tutto accidentalmente, mentre stava piegando una pagina del libro (così che una parte di quella successiva fosse visibile). In quel momento si accorse che il titolo originale – nell’edizione ottocentesca la scritta “A Human Document” è riportata nell’intestazione di ogni pagina – appariva ora come A Humument: “una parola terrosa che riecheggia l’Umano e il Monumento, e che allo stesso tempo ha un certo che di squadrato, o forse di riesumato per finire in quelle stanze del mondo degli archivi dove sono conservati i documenti” (Tom Phillips, postfazione). Non poteva esserci titolo migliore.

Abbiamo già visto sopra che il debutto pubblico di “A Humument” risale al 1973, all’Institute of Contemporary Arts. In quei primi anni di diffusione ancora abbastanza underground alcune sue tavole finirono, come sappiamo, anche nelle copertine dei dischi (oltre a Starless and Bible Black, lo si trova anche in No Pussyfooting di Fripp e Eno, dove si intravedono tre pagine). Col tempo, mentre la fama dello Humument aumentava e Tom Phillips portava avanti il suo progetto lungo un’intera vita che prevedeva una continua opera di rielaborazione del suo lavoro, arrivò anche la prima edizione acquistabile sul mercato (1980), cui fecero seguito altre quattro edizioni (1987, 1997, 2005, 2012), ognuna diversa da quelle precedenti (Phillips si era posto come regola che in ciascuna edizione avrebbe dovuto modificare ogni pagina – cosa che negli anni si rivelò sempre più complessa). In tutto ciò vari benefattori, ammiratori e amici si erano messi a recuperare le vecchie edizioni ottocentesche del romanzo di Mallock per farne dono a Phillips così che potesse continuare il suo progetto. Come si può facilmente immaginare, dopo alcuni anni quel libro dimenticato non valeva più tre miseri pence ma qualche migliaio di sterline!

Infine nel 2016 – in epoca ormai pienamente digitale – Phillips giunse al compimento della sua opera con l’edizione definitiva (la sesta e ultima quindi, tra quelle “commerciali”), che è precisamente quella acquistabile oggi (attualmente in ristampa del 2023).

La frase “this night wounds time,” a pagina 222 è sempre lì, dopo cinquant’anni dall’inizio di questa storia.

Tom Phillips invece se ne è andato il 28 novembre 2022, raggiungendo l’amico/fantasma di una vita, il romanziere dimenticato T.A.Mallock:

“pensa ai sistemi che ammutoliscono

pensa all’arcobaleno oscuro, toge

dedicato al solo e unico generatore di questo libro

dalle cui ossa le mie ossa

le mie migliori, sono ora perpetue

il tuo sepolcro fuso nel mio

pagina per pagina”

(Tavola di dedica, pagina 367)*

*il romanzo Humument finisce a pagina 366, una pagina per ogni giorno di un anno bisestile.

3) “This night wounds time,” (cosa accade a pagina 222)

E quindi il trait d’union tra Humument e i King Crimson è una frase di sole quattro parole (più una virgola) incastonate in una macchia bianca. Nel testo originale, quello di Mallock, le parole si trovano in quattro righe successive, e sono grosso modo disposte una sotto l’altra. Anche su di esse Phillips interviene secondo quello che è il suo modo tipico di alterare il testo di Mallock: una volta individuate le parole di suo interesse in una certa pagina, Phillips procede a nascondere o comunque oscurare tutte le altre con colori, disegni, collage, textures spesso complesse (e, spesso, semanticamente rilevanti). A questo punto Phillips disegna attorno alle parole “salvate” un fondo bianco, che può apparire simile a una macchia, o alla tessera mancante di un puzzle, o ancora ad una nuvola frastagliata, e se necessario collega le varie parole per il tramite di “canali” o percorsi (sempre in tinta bianca), così da formare delle frasi del tutto nuove rispetto a quelle del testo originale. Normalmente al termine di questo lavoro emergono in ciascuna pagina cinque o sei frasi più o meno complete, più o meno perspicue.

Ecco cosa si legga a pagina 222:

this night wounds time,

libera me

libera me

throw chance away

And for what? This man of her yesterday

me? I should have felt less

Che grosso modo sembra voler dire: “questa notte ferisce il tempo, liberami, liberami: getta via il caso. Ma per cosa poi? Questo uomo del suo ieri [suo di Irma], questo uomo, che sono io, avrebbe dovuto sentire di meno”.

Qual è il significato di questa pagina? E, forse ancora più importante, quali strategie deve (può) mettere in atto il lettore per conferire senso a questo strano testo?

Si può fare un tentativo – il più ovvio – con la lettura sequenziale.

Proviamoci: a pagina 221 il narratore aveva fatto riferimento sia a Toge che a se stesso in merito ad una lettera promessa (scritta da Irma?), ad un fidanzamento monco (un “gagemen”, in luogo dell’“engagement”), e ancora a tenere circostanze contrapposte all’ossessione per l’amata (“tender circumstances”… “she taxed his mind”). Poi viene la nostra pagina 222, dove il narratore ci parla chiaramente di una sua condizione tormentosa (per amore?). Quindi a pagina 223 ritroviamo il narratore (o piuttosto Bill Toge? O forse sono la stessa persona?) che continua a riflettere sulle sue difficoltà sentimentali con Irma: “non so razionare le mie armi di conforto, sono tutt’occhi con lacrime dentro. È il tempo del dolore” etc.

Insomma, si può dire che la lettura sequenziale di questa parte del libro racconti il tormento interiore del narratore e di Bill Toge e (nelle pagine che seguiranno) di Irma: Three of a Perfect Pair, mi verrebbe da dire, con quelle tendenze schizofreniche tipiche delle relazioni complicate, gravose, in definitiva prive di speranza, che troveranno memorabile descrizione in una canzone di una decina di anni successiva...

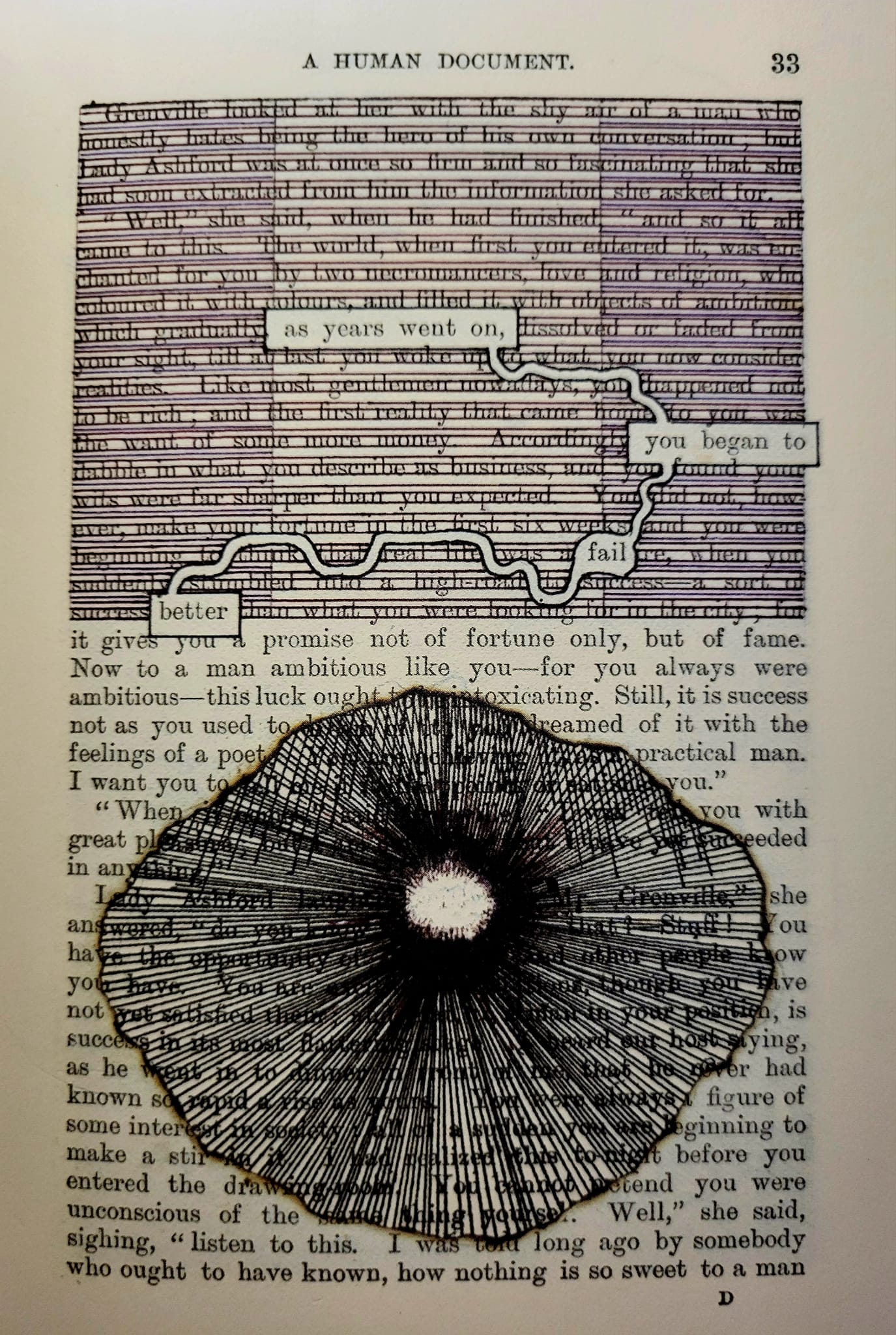

Non è affatto detto però che questa sia la strategia di lettura migliore. Anzi, una cosa è certa: sappiamo che nel processo di trasformazione dello Human Document di Mallock nel suo Humument, Tom Phillips ha lavorato proprio rifiutando la strategia “ovvia” del procedimento sequenziale. Spiega altresì di essersi ispirato ad una frase qui, ad una parola lì, alla suggestione di un brano, senza seguire un ordine preciso. E d’altronde la prima pagina cui mise mano è la numero 33. Possiamo quindi dire con una certa ragione che la “vera” prima frase del romanzo Humument non sia “I sing a book of the art that was” (p.1) ma “as years went on, you began to fail better” (p.33), chissà, forse un’inconsapevole epitome autoironica di quelli che sarebbero stati i successivi cinquant’anni della vita dell’autore. Forse – più in generale – il destino di ogni artista.

Sia come sia, ho compreso con chiarezza che questo libro lascia sì la libertà ai suoi lettori di farci il picnic da loro preferito, ma richiede comunque che quegli stessi lettori rispettino alcune regole di buon comportamento quando vi si addentrano: 1) lasciar lavorare il tempo (non aver cioè fretta di capire), 2) far emergere la cooperazione tra testo e disegno, 3) costruire il proprio testo (i propri testi) sapendo che la storia di Irma e Bill Toge è in realtà un pretesto usato da Phillips per sviluppare la sua riflessione sul ruolo della musica e dell’arte nella vita, e sul ruolo del caso e del sogno nel progettare proprio degli esseri umani. È d’altro canto anche un metatesto ricchissimo di citazioni spesso ben nascoste, dall’Ulisse di Joyce a Mallarmé a Dante, a molti altri che non è dato scoprire subito.

4) A throw of dice will never do away with chance (cos’hanno in comune lo Humument e i King Crimson?)

Perché questa notte ferisce il tempo? Bene in vista, eppure nascosta nei disegni di sfondo, sempre a pagina 222 c’è una frase ulteriore, non appartenente al testo originale di Mallock, ma disegnata da Phillips in guisa di segni incastonati all’interno di cinque cerchi bianchi, tali che ad una prima occhiata potrebbero sembrare dei tratti decorativi. Questa è la frase: “A throw of dice will never do away with chance”, che è un’ingegnosa traduzione in inglese del titolo della poesia di Mallarmé “Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard” (Un tiro di dadi non abolirà mai il caso). Ancora il caso quindi, e la sua ineluttabilità. E la poesia che, nel 1897, segna l’inizio nella letteratura occidentale della combinazione tra verso libero, sperimentazione tipografica e grafica, anticipando di settant’anni il lavoro di Phillips e, più in generale, le gloriose vicende dell’allora non ancora nato Graphic Design.

In questa corsa invero un po’ accidentata lungo i meandri di arte, grafica, musica (e amore) emergono così casualmente (in figura, o nello sfondo) alcuni elementi comuni allo Humument di Phillips e ai King Crimson (non solo quelli del 1973-1974).

a) La notte – la notte è una delle chiavi tematiche di Starless and Bible Black/Red. E il verso “this night wounds time,” richiama uno dei nuclei tematici fondamentali di “Under Milk Wood” di Dylan Thomas, che è circolarmente costruito attorno alla notte;

b) Il Tempo – non sfugge che le sei forme del King Crimson Eterno (e l’invisibile settima) che si manifestano nel tempo (nei decenni) e le strategie di sviluppo dello Humument lungo cinquant’anni sono accomunate dal lasciarsi venire (liberamente) all’essere. Il loro fruitore (ascoltatore, lettore) se vuole rovinare tutto, può pretendere di capire tutto, violando il compito cooperativo di non avere fretta; se invece vuole rimanere in discorso con il testo King Crimson e il testo Humument, devi regalarsi tempo;

c) Regola e Caso – l’improvvisazione ha avuto un ruolo fondamentale nell’identità dei King Crimson – prima, durante e dopo il (breve) periodo Muir/Bruford. L’improvvisazione è legata a regole (implicite) ancora più ferree dell’esecuzione del repertorio;

d) Incorporare, rielaborare, sviluppare – la pubblicazione dello sterminato materiale di studio, delle takes alternative, dei concerti etc etc. dei King Crimson, rivela lo sviluppo e la rielaborazione negli anni di motivi magari solo accennati anche decenni prima (in ciò ricordandoci da vicino lo sviluppo cinquantennale dello Humument). Similmente, testi, musica e cover art incorporano e rielaborano esperienze letterarie e musicali – un po’ come “The Devil’s Triangle” riprende “Mars Bringer of War” dalla suite “Planets” di Gustav Holst, o come Phillips riprende il monologo finale di Molly Bloom dall’Ulisse di Joyce per l’ultima pagina di Humument (la tavola 366).

e) Sfondo e figura (il resto bianco) – non tutto ciò che è in primo piano è essenziale, non tutto ciò che è nello sfondo è complementare. Alcune delle osservazioni fondamentali dello Humument sono nascoste nello sfondo; similmente alcuni dei contributi fondamentali nella musica dei King Crimson si trovano a volte nell’astenersi dal suonare (capitò a Bruford) a volte nel suonare “nello sfondo”, come il fairy dusting di Bill Rieflin negli ultimi King Crimson: lo sciocco si affretta a farci sapere che non capisce il senso di quei contributi, chi è più accorto invece tace e continua ad addentrarsi nella foresta di suoni fino a quando non avrà raggiunto la radura.

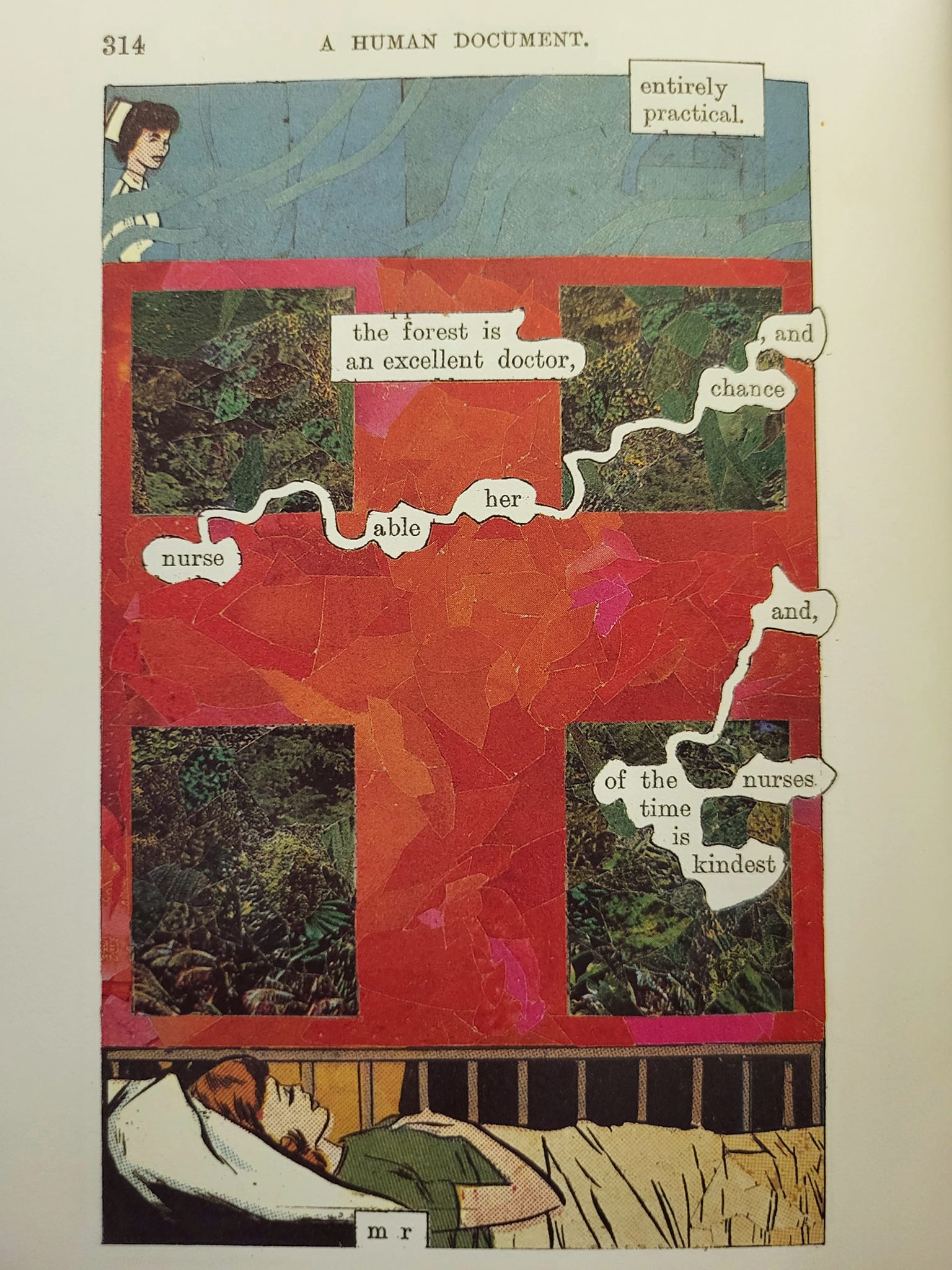

“The forest is an excellent doctor, and chance her able nurse and, of the nurses, time is the kindest”

- ENGLISH VERSION -

King Crimson and the Humument: a somewhat bumpy ride in the roundabouts of art and music

It’s no secret that “Under Milk Wood” by Dylan Thomas - one of the most revolutionary radio plays of the Post Second World War years - is cited in King Crimson’s albums “Starless and Bible Black” and “Red”, having its incipit provided to the former the title of both the album and the seventh song, and to the latter a powerful inspiration for the lyrics of “Starless”, one of the band’s most celebrated songs and the last ever performed by King Crimson themselves (8 December 2021, Tōkyō). It may be instead a bit less known the particular contribution of Tom Phillips’ “A Humument” to King Crimson’s extraordinary creative age of the years 1973 and 1974.

Since no one would be possibly able to give a truly satisfactory definition of this book, I think it is worth introducing it with the words of Brian Eno: “A Humument is one of the most original, fascinating and enchanting books of all time”. At the same time, I will define here with a certain degree of approximation this “Human Monument/Human Document” as a work of art – an art book, or even an experimental novel – created over a period of fifty years, between 1966 and 2016, and made up of 366 pages (plus an elaborated dedication on page 367) of which currently every ordinary human being may buy at very little cost a full color copy thanks to the publisher Thames & Hudson (“A Humument – A Treated Victorian Novel”, Definitive Edition: London, 2016; reprint 2023).

The story, obviously, does not end here, therefore for those who are intrigued by the serendipity with which the paths of literature and art sometimes meet those of (great) music, I will now say in order i) what the Humument has to do with King Crimson; ii) how the Humument was born (and what it is); iii) what happens on page 222 of the book; iv) whether, finally, there is something in common between the Humument project and King Crimson.

i) First things first: what does “A Humument” have to do with King Crimson?

The back cover of “Starless and Bible Black” (1974) features a writing well known to all crim-heads: “this night wounds time,”. The writing is found inside what appears to be a spot of white paint and this in turn is found inside a colored board at the bottom of which various poorly legible letters can be glimpsed.

This graphic work is in fact a detail of page 222 of “A Humument – A Treated Victorian Novel” by Tom Phillips, which at the time of “Starless and Bible Black” had recently been published in its first “almost complete” edition (Tetrad Publishing House, 1973, non-commercial edition; between 1971 and 1974 Tetrad oversaw the publication of all, so to speak, the “advancements” of the Humument) and above all it had been exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London (1973). Significantly, King Crimson of 1973-1974 – true avant-gardists at this point largely unrelated to the traditional prog world with which they had been, more or less correctly, associated in previous years – chose as SABB’s cover art an experimental work which would acquire fame and notoriety only several years later.

ii) So what is “A Humument” and where does it come from?

Easy said: “A Humument” is a book written between the 20th and 21st centuries that ate another book, the three-volume work “A Human Document” by the Victorian novelist W.H. Mallock, which was written towards the end of the 19th century.

These are the facts: in 1966, three years before “In the Court of the Crimson King” and eight years before “Starless and Bible Black” were published, a twenty-nine-year-old graphic designer/painter/printer named Tom Phillips had developed a project. Fascinated as he was by the literary experiences of Burroughs and the musical experimentations of John Cage, he wanted to explore the role of chance, of randomness, in the process of producing a work of art. For his project there was a need for a large book, possibly a novel, possibly old but still in good condition, to be "treated", that is, to be altered by modifying each page with painting, collage and cutting techniques so as to create a completely new book, keeping only some words legible on each page and linking them together to create a new text.

On November 5th Tom Phillips was wandering around one of those warehouses where old furniture, bookcases, the remains of some value coming from cleared out cellars and attics are piled up, and he had decided that the first book he found was on sale at the price of three pence would become the basic material for his project. As chance would have it, he came across the novel “A Human Document” by a W.H. Mallock, 1892 (ninth edition). Phillips had not the slightest idea who this Mallock was, but the fact that his work had had at least nine editions indicated that he must have been quite famous at the end of the nineteenth century. In addition, the fact that just seven decades later the book he held in his hands had been almost completely forgotten made it particularly fascinating to Phillips. Furthermore, there was an exquisitely technical detail that made “A Human Document” the ideal novel for his project: it had been printed - as it was often the case at the time - with a wide spacing between characters, which almost miraculously met the needs of the young artist. Finally, it cost exactly three pence, which was Phillips’ initial condicio sine qua non!

On the other hand, chance as a causal factor in the process of producing a work of art has relevance only if it is also accompanied by a precise and meaningful system of constraints (an example: Philip K. Dick used “suggestions”/ rules dictated to him by the I Ching to shape the subject and plot of “The Man in the High Castle” – “The Swastika on the Sun”), in the absence of which the project would be just a children’s game. In the case of “A Humument” the constraints are multiple, both on graphic and textual level; I will mention here only the constraint/rule according to which every time the word “together” appears in the original text, Phillips must delete/hide a part of the word (-ther) so as to bring Toge into the scene, Bill Toge, who in “A Humument” is the secondary character of the story, the main being Irma, a legacy of Mallock’s pre-existing novel.

Ah, still on “chance”. Phillips stumbled upon the title of his work quite accidentally: while he was folding a page of the book so that part of the next one was visible, he noticed that the original title –

in the nineteenth-century edition the writing “A HUMAN DOCUMENT” is shown in the header of each page – now appeared as A HUMUMENT, “an earthy word which echoes of humanity and monument as well as a sense of something hewn, or exhumed to end up in the muniment rooms of the archived world” (Tom Phillips, afterword). There couldn’t be a better title.

It was said above that the public debut of “A Humument” dates back to 1973, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts. In those first years of still quite underground diffusion, some of its pages ended up, as we know, also on record covers (in addition to Starless and Bible Black, the Humument featured in “No Pussyfooting” by Fripp and Eno, where three pages can be glimpsed). While Tom Phillips carried on his lifelong project, which was in fact a continuous reworking of the Humument, its fame increased. The first edition that could be purchased on the market was published on 1980, and it is was followed by four more editions (1987, 1997, 2005, 2012), each different from the previous ones (Phillips had made it a rule that in each edition he would have to modify every page – something which over the years proved to be increasingly complex). Over time patrons, admirers and friends recovered copies of the nineteenth-century editions of Mallock’s novel and donated them to Phillips so that he could continue his project. Quite obviously, after a few years that forgotten book was no longer worth a paltry three pence but a few thousand pounds!

Finally in 2016 – in the digital era – Phillips reached the completion of his work with the definitive edition (the sixth and last therefore, among the “commercial” ones), which is precisely the one that can be purchased today (currently in a 2023 reprint).

The phrase “this night wounds time,” on page 222 is still there, fifty years after the beginning of this story.

Tom Phillips instead passed away on November 28, 2022, joining the friend/ghost of a lifetime, the forgotten novelist T.A.Mallock:

“think of the systems mute

think of the dark rainbow, toge

dedication - TO THE SOLE AND ONLY BEGETTER OF THIS VOLUME

by whose bones my bones

my best, perpetuate

your grave in mine fused

page for page”

(Dedication, page 367)*

*the novel Humument ends on page 366, one page for each day of a leap year.

iii) “This night wounds time,” (the eventful page 222)

The trait d'union between Humument and King Crimson is a phrase of only four words (plus a comma) set in a white spot. In the original text these four words are found in four successive lines, and are roughly arranged one below the other. Phillips makes them emerge from the original text using his standard method of altering Mallock’s text: once he has identified on a certain page the words that will form the new next, Phillips proceeds to hide or at least obscure all the others with colours, drawings, collages, often complex (and often semantically relevant) textures. At this point Phillips draws a white background around the “spared” words, which may appear similar to a stain, or to the missing piece of a puzzle, or even to a jagged cloud, and if necessary connects the various words by means of “channels” or paths (always in white), so as to form completely new sentences. Normally at the end of this work five or six sentences emerge on each page, more or less complete, more or less perspicuous.

Here is what we read on page 222:

“this night wounds time,

libera me

libera me

throw chance away

And for what? This man of her yesterday

myself? I should have felt less”

Which roughly seems to mean: “this night wounds time, free me, free me: throw away the chance. But for what then? This man of her (Irma)’s yesterday, this man, who is me, should have felt less.”

What is the meaning of this page? And, possibly more important, what strategies should the reader implement to let this peculiar text making sense?

An obvious strategy may be sequential reading.

Let’s see: on page 221 the narrator appears to make reference both to Toge and himself regarding a certain promised letter (written by Irma?), a broken engagement (a “gagemen” in the text), and sweet circumstances as opposed to the obsession for the beloved (“tender circumstances”… “she taxed his mind”). Then comes our page 222, where the narrator clearly tells us about a tormenting condition of his (for love?). Finally, on page 223 we find the narrator (or rather Bill Toge? Unless Toge and the narrator are the same person…) who continues to reflect on his sentimental difficulties with Irma: “I can’t ration my confort weapons, all all eyes with tears in them. Pain time” etc.

In short, it can be said that the sequential reading of this part of the book tells the inner torment of the narrator and of Bill Toge and (in the following pages) of Irma: “Three of a Perfect Pair”, I would say, with those typical schizophrenic tendencies of complicated, aggravated, ultimately hopeless relationships, which will find a memorable description in a song from about ten years later...

This said, I am pretty sure sequential reading is not the best strategy to approach “A Humument”. Indeed, one thing is certain: we know that in the process of transforming Mallock’s Human Document into his Humument, Tom Phillips worked precisely by rejecting the “obvious” strategy of the sequential procedure. He also explains that he was inspired by a phrase here, a word there, the suggestion of a passage, without following a precise order. And on the other hand, he started his work by altering page 33. We can therefore say with some reason that the “real” first sentence of the novel Humument is not “I sing a book of the art that was” (p.1) but “as years went on, you began to fail better” (p.33)… who knows, perhaps an unconscious self-deprecating epitome of what would have been the next fifty years of the author’s life. Perhaps – more generally – the destiny of every artist.

Be that as it may, I clearly understood that this book gives its readers the freedom to have their favorite picnic, but it still requires that those same readers respect some rules of good behavior when they delve into it: 1) let time work (that is, do not rush to understand), 2) bring out the cooperation between text and drawing, 3) build your own text (your own texts), while knowing that the story of Irma and Bill Toge is, eventually, just a pretext for Phillips to develop his reflection on the role of music and art in life, and on the role of chance and dreams in the projects of human beings. On the other hand, it is also a metatext which is full of often hidden quotations, from Joyce’s Ulysses to Mallarmé to Dante, to many others that cannot be discovered immediately.

iv) A throw of dice will never do away with chance (what do Humument and King Crimson have in common?)

Why does this night wounds time? On page 222, clearly visible, yet hidden in the background drawings, there is a further sentence, not belonging to Mallock’s original text, but drawn by Phillips in the form of signs set inside five white circles, such that at first glance they might seem like decorative features. This is the phrase: “A throw of dice will never do away with chance”, which is an ingenious translation into English of the title of Mallarmé’s poem “Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard” (A throw of dice will never abolish the case). Still the chance then, and its inevitability. And the poetry that, in 1897, marks the beginning in Western Literature of the combination of free verse and typographical and graphic experimentation, anticipating Phillips’ work by seventy years and, more generally, the glorious events of the then unborn Graphic Design.

In this admittedly somewhat bumpy ride along the meanders of art, graphics, music (and love) some elements emerge randomly (in the figure, or in the background) that are common to Phillips’ Humument and King Crimson (and not just those of 1973-1974).

a) Night – night is one of the thematic keys of “Starless and Bible Black” and “Red”. And the line “this night wounds time,” recalls one of the fundamental thematic nuclei of “Under Milk Wood” by Dylan Thomas, which is circularly built around the night;

b) Time – it is clear that the six forms of the Eternal King Crimson (and the Invisible Seventh) that manifest themselves over time (over decades) and the development strategies of Humument over fifty years are united by letting themselves come (freely) to Being. If their users (listeners, readers) want to ruin everything, they can claim to understand everything, violating the cooperative task of not being in a hurry; those instead who accept to stay in conversation with the King Crimson text and the Humument text, have to allow themselves time;

c) Rule and Chance – improvisation played a fundamental role in King Crimson’s identity – before, during and after the (brief) Muir/Bruford tenure of the percussion section. Improvisation is linked to (implicit) rules even tighter than performing the repertoire is;

d) Incorporate, rework, develop – the publication of the endless study material, alternative takes, concerts etc etc. by King Crimson, reveals the development and reworking over the years of motifs sometimes just alluded decades earlier (in this closely reminding us of the fifty-year development of Humument). Similarly, lyrics, music and cover art incorporate and rework literary and musical experiences – like “The Devil's Triangle” takes up “Mars Bringer of War” from Gustav Holst’s “Planets” suite, or how Phillips takes up Molly Bloom’s final monologue from Joyce’s Ulysses for the last page of Humument (p. 366).

e) Background and figure – not everything in the foreground is essential, not everything in the background is complementary. Some of Humument’s key observations are hidden in the background; similarly some of the fundamental contributions in King Crimson’s music are sometimes found in abstaining from playing (it happened to Bruford), sometimes in playing “in the background”, like Bill Rieflin’s fairy dusting in the later King Crimson. The fool hastens to let us know that he doesn’t understand the meaning of those contributions. Instead, those who are more aware remain silent and continue to enter the forest of sounds until they reach the clearing.

“The forest is an excellent doctor, and chance her able nurse and, of the nurses, time is the kindest”.